Chapter 2: Community and Historical Ecology

Historic Impacts and Restoration Efforts

Timeline of Land and Water Management in the Lake Superior NERR

Expand each section of the timeline to explore historic photos and documents related to the history of the Lake Superior Reserve

Indigenous Communities and Landscapes

North American Fur Trade

Treaties

Resource Extraction, Industrialization, and Colonization

Restoration

I. History of Land and Water Management

Pre-Industrial Resources

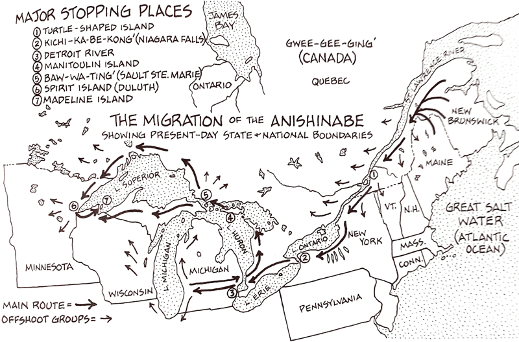

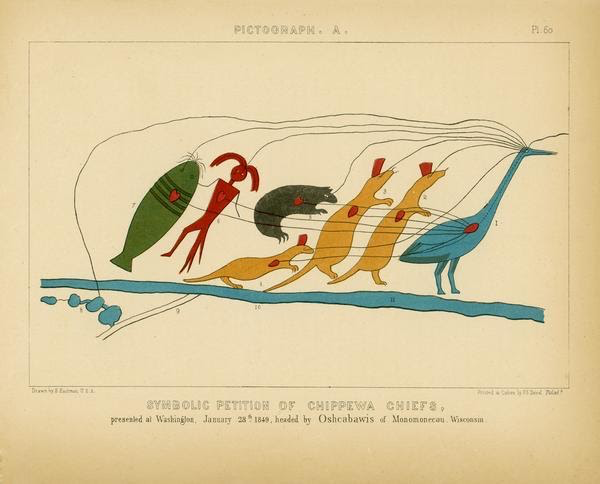

Like estuaries globally, the St. Louis River estuary has been economically, culturally and spiritually important for Indigenous people throughout its existence. The original inhabitants are believed to have been members of Paleo-Indian cultures, followed by people of the Old Copper Culture, who hunted with spear points and knives and fished with metal hooks. Around 2,000 years ago, Woodlands people, known for burial mounds and pottery, lived in the area.

In 1854, the Lake Superior Ojibwe and the U.S. government negotiated and signed the Treaty of LaPointe, establishing reservations and opening the region to colonization. The treaty ceded Anishinaabe lands to the United States in Northeastern Minnesota, in exchange for reservations in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota. Tribal Nations retain rights to hunt, fish, gather and practice traditional lifeways within the Ceded Territory, including Chi-gami ziibi, the St. Louis River estuary.

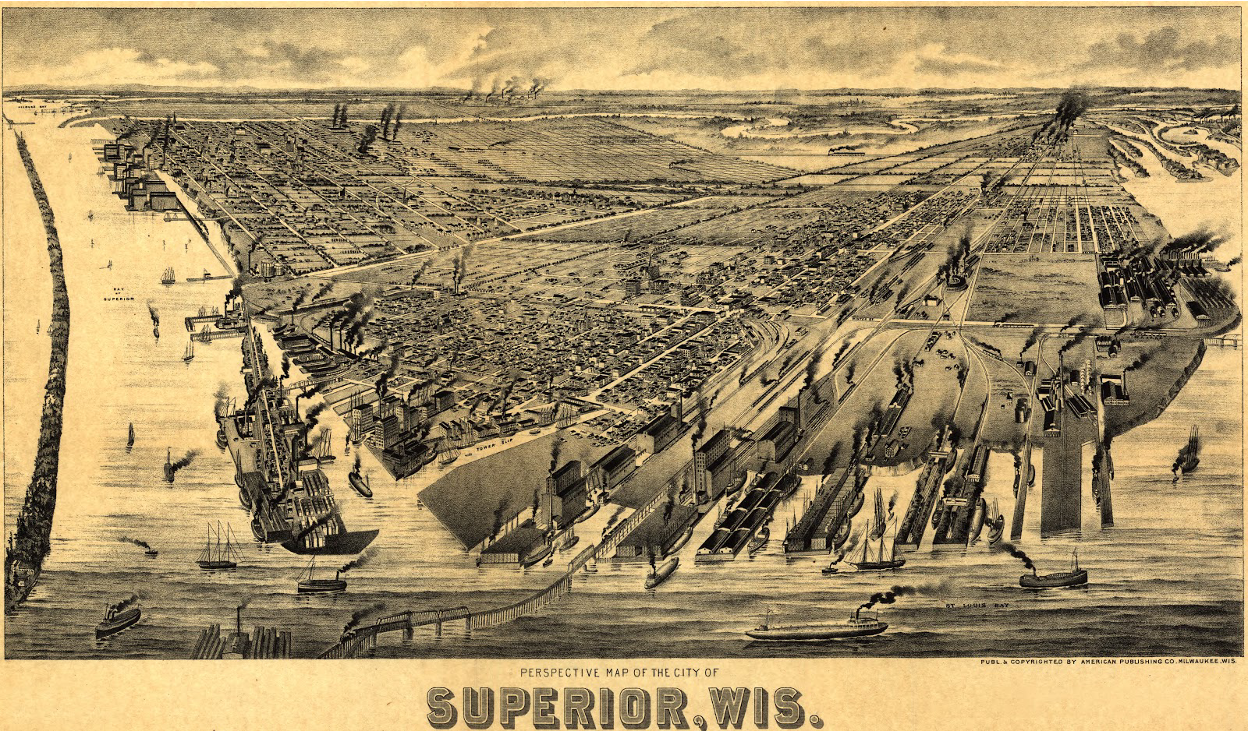

Towns quickly grew on either side of the St. Louis River. By 1857, Superior had a population of over 2,000, while Duluth grew less rapidly. The construction of roads, locks, railroads, and a ship canal made it possible for the area to take advantage of its position and become a primary port for the region’s natural resources. Major industries that dominated the Duluth-Superior area starting in the 1850’s included sawmills due to logging from the extensive forests of Minnesota and Wisconsin, and shipping of Midwestern grain, iron ore from Minnesota, steel, coal, and eventually petroleum products.

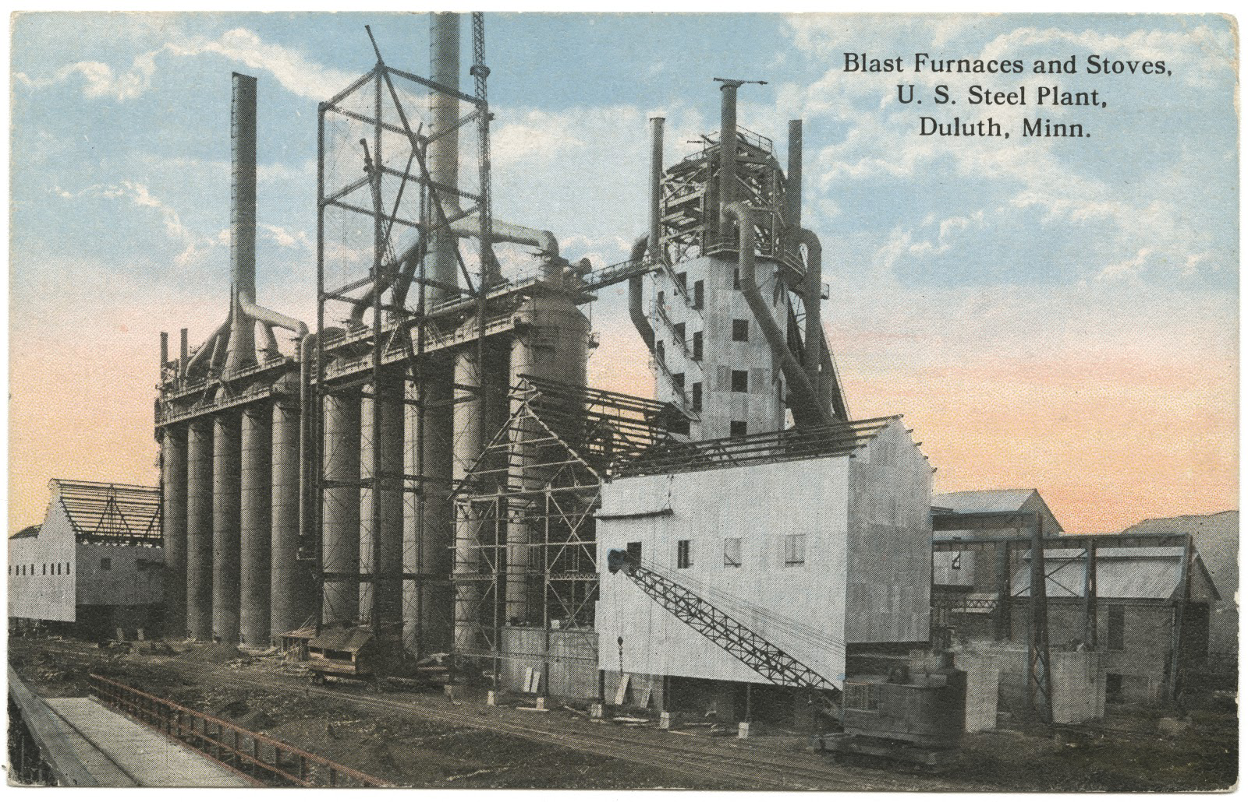

Industry continued to grow along the St. Louis River in the late 1800s. The first railroad arrived in 1870, and ships navigated Superior Bay. Sawmills, oil refineries, iron ore docks, paint factories, steel and paper mills, and meat-packing plants were built along the banks. The U.S. Steel Duluth Works plant opened on the western shore of Spirit Lake in 1915, with bold plans to smelt ore from Minnesota iron mines in the upper reaches of the St. Louis River. A coke plant and other industries also developed here. Protected from the fierce lake wind, these industries kept profit and jobs in Minnesota by not shipping ore to plants in Ohio and other Midwestern states. But in a time with little protective regulation, waste was released into the river. While the steel plant operated, it released a variety of pollutants into Spirit Lake. These included heavy metals such as lead, copper, and zinc, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). Natural habitat and wetlands disappeared and pollutants lingered in the sediment. By the 1970s, the river was considered dead. Floating sewage and smelly water kept people away from the shore. More complete treatment of wastewater began in 1978. By 1981, people began to fish and boat on the river again.

II. Restoration Efforts in the Reserve

In 1987, the St. Louis River was designated one of 43 impaired Areas of Concerns in the Great Lakes, and 9 beneficial-use impairments (BUIs) were identified of which 3 have since been removed. The U.S.-Canada Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement defines Areas of Concern as "geographic areas designated by the Parties (ie US and Canada) where significant impairment of beneficial uses has occurred as a result of human activities at the local level." An AOC is a location that has experienced environmental degradation (US EPA, 2022). Wisconsin and Minnesota state agencies, tribal agencies, federal authorities, engaged private sector entities, and nonprofits are working to remove the remaining BUIs from legacy pollution and restore habitat. To restore the river, these partners are remediating polluted sediment, planting wild rice, monitoring fish and wildlife, and restoring habitat. The ongoing clean-up of the St. Louis River—while maintaining a busy port—is an achievement that demonstrates social and political commitment to the estuary and Lake Superior.

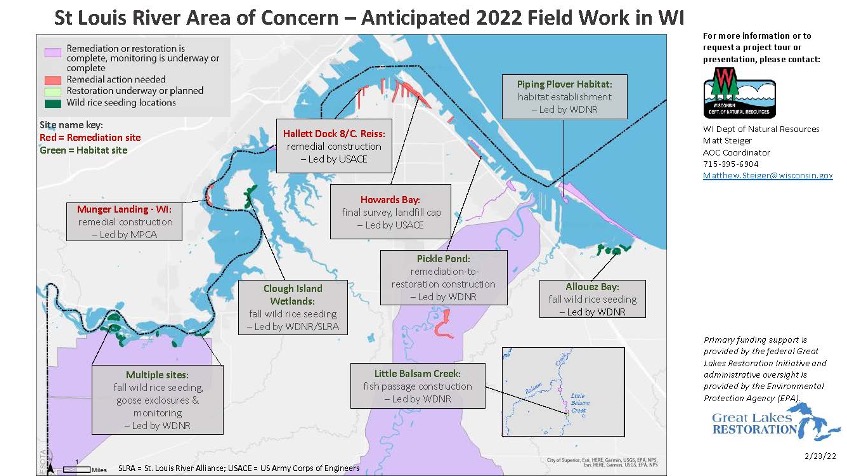

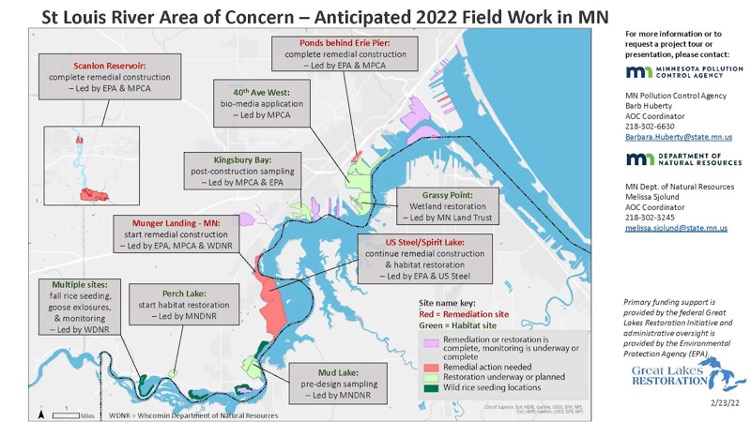

St. Louis AOC

St. Louis River Area of Concern projects to remediate contaminants and restore habitat in 2022. Projects are led by the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources, Minnesota Department of Natural Resources and Pollution Control Agency with support from many other partners including the St. Louis River Alliance and the Reserve. (Credit: Minnesota and Wisconsin DNRs)

Beneficial use impairments in the St. Louis River Area of Concern include:

- Restrictions on Fish and Wildlife Consumption

- Degraded Fish and Wildlife Populations

- Louis River Fish Tumors BUI Removals - Removed 2019

- Degradation of Benthos

- Restrictions on Dredging Activities

- St. Louis River Eutrophication or Undesirable Algae - Removed 2020

- Beach Closings

- Degradation of Aesthetics - Removed 2014

- Loss of Fish and Wildlife Habitat

Existing Restoration Activities

The St. Louis River Habitat Workgroup created and maintains an updated website showing past, current and planned restoration activities for the estuary. The map of these projects is shown below.

III. Land and Water Stewardship and Conservation Activities

The land within the Reserve boundaries is entirely publicly or tribally owned, and is protected by authorities specific to each of the landholders. These authorities provide the long-term protection of the Reserve’s estuarine resources necessary to ensure a stable environment for research. The water area within the boundaries is protected by state and local laws governing recreational and commercial uses and public access. Surveillance and enforcement is the responsibility of the respective landowners, as well as the community law enforcement departments of the city of Superior, Douglas County, GLIFWC, UW-Superior, and the WDNR. These agencies will continue to be responsible for enforcement in their respective jurisdictions.

Two portions of the Reserve are designated State Natural Areas. These SNAs protect outstanding examples of natural communities and provide refuges for rare plants and animals. A high level of protection is afforded by legal dedication of SNAs through Articles of Dedication, a special kind of perpetual conservation easement. Both Lake Superior and the St. Louis River are subject to the protections of the public trust doctrine as outlined in the State Constitution. The water areas of the Reserve are managed under this authority.

In 2021, the Lake Superior Reserve initiated a stewardship program. The Stewardship program at the Lake Superior Reserve enhances resiliency of the St. Louis River estuary by working closely with landholding partners and Ceded Territory rights holders to understand and respond to the needs of our community, both human and natural.

Within the Reserve System, Stewardship Coordinators (SCs) have diverse but critical roles in public engagement, restoration-related research and monitoring, habitat manipulation, vulnerability assessments, land management, and public access. SCs’ work on include:

- Restoration, including restoration implementation, increasing scientific understanding of restoration, and outreach

- Sentinel Site Monitoring to understand how wetland vegetation communities are affected by local water level and inundation trends

- Habitat Mapping and Change. Mapping habitat in reserve and watershed boundaries to characterize and communicate short-term variability (1-10 years) and long-term trends (10+ years) in the spatial changes in reserve habitats. Examine the impacts of climate change, land use within adjacent watersheds, and changes in local water-level and inundation patterns on reserve habitats

- Vulnerability Assessments, using tools to assess vulnerability of Reserve habitats to threats such as climate change, and develop appropriate adaptation strategies

- Land acquisition, focusing on protecting key estuarine and coastal habitats, maintaining biodiversity, and enhancing habitat connectivity

- On-Site Stewardship and Conservation Actions, such as managing invasive species, reducing environmental stressors, and monitoring habitat resilience and change

In November of 2021, President Biden signed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act into law, allocating $77 million for NERRS restoration and conservation over five years- roughly $15 million per year. Funding internal the the Reserve system will support restoration of estuarine habitat and purchase of lands for conservation in alignment with Wisconsin’s Coastal and Estuarine Land Conservation Plan (Wisconsin Coastal Management Program, 2011).

With most AOC projects planned to be completed by the end of 2025, lower St. Louis River partners were convened by the Minnesota Land Trust in 2019-22 to establish the Lake Superior Headwaters Sustainability Partnership. The Headwaters Partnership, as it’s known, is designed to facilitate the transition from delisting the St. Louis River Area of Concern to a future where conservation and natural resources work in the region continues to sustain and build upon this accomplishment. The Partnership works to address ongoing and emerging threats and opportunities facing the Lake Superior Headwaters region related to natural resources and the associated intersections with the economy and community health and well-being through partnerships and coordination.

RESERVE RESILIENCE

I. Coastal Adaptations and Living Shorelines

A primary step toward coastal adaptation amid fluctuating water levels in the Great Lakes is understanding past conditions and anticipating future ones. The Reserve works to provide a visual monitoring record of changes through a lake level documentation using georeferenced photos. The viewer provides an overview of conditions over time as lake levels rise and fall, supporting better land use decisions.

The viewer was developed in 2020 by UW-Superior Student Undergraduate Research Fellow Sara Rybak with support from Coastal Training Program Coordinator Karina Heim.

II. Disaster Preparedness

Potential disasters in the lower St. Louis River include extreme flooding, drought, industrial spills or fires.

U.S. Coast Guard (USCG), Marine Safety Unit, Duluth The USCG in Duluth has a Memorandum of Agreement with the Reserve through approval by UW–Madison Division of Extension and UW-Superior, to support their Continuity of Operations planning in the region. In the early summer of 2019, the USCG approached the Reserve with a need for a facility that could serve as a mustering station and site of operations during disaster response and recovery. It was determined that the Reserve’s Confluence Room inside the Estuarium met the USCG requirements and the location also provided access to the dock. The agreement stipulates that the USCG may operate around the clock out of this facility for a period of no more than thirty consecutive days.